Why has religious radicalism flourished in Indonesia since the Reform Era?

Alexandre Pelletier, a researcher from Cornell University, USA, sought answers through a study focusing on the mobilization of fundamentalist Islam in Java. The results of his research, conducted in 2014-2015 as part of his doctoral program, were recently published in Comparative Politics.

Pelletier’s findings are not entirely surprising. They reinforce assumptions widely held by the public. His research points to West Java as a particularly fertile ground for religious radicalism and militant groups compared to regions like East Java or Central Java.

One intriguing conclusion from Pelletier’s research is that religious radicalism tends to thrive in communities where religious authority is weak. In other words, in areas where religious leaders and institutions lack dominant influence, or are competing for authority, radicalism finds fertile ground.

Pelletier studied the mobilization of fundamentalist Islamic groups across Java, with one of the most prominent examples being the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI). He describes FPI as a militant group known for mobilizing—often violently—against what they deem immoral or deviant.

Pelletier also highlights that groups like FPI and other militant organizations have played a significant role in heightening religious polarization and populism in Indonesia, which had little room to grow before the Reform Era.

Pelletier’s study shows that out of the six provinces in Java, West Java has the highest concentration of militant Islamic groups and the most frequent instances of mass mobilization. Some areas around West Java have experienced rapid growth in fundamentalist Islamic groups and consistent mobilization efforts.

According to Pelletier, nearly 60% of violent mobilization incidents in Java since 1998 have occurred in West Java, compared to only 10% in East Java.

Pelletier’s conclusions challenge the theory that militant groups like FPI emerged primarily as a result of decentralization and political patronage during the Reform Era. The reality, according to his research, is that these groups have flourished more in West Java, despite political incentives being similar across Indonesia.

He also questions another theory that links the rise of militant groups in West Java to the legacy of Darul Islam, a hardline movement that sought to establish an Islamic state in Indonesia between 1942 and 1962. Pelletier found only a limited correlation between the two. In fact, most leaders of militant groups, particularly at the district and sub-district levels, were clerics (kiai or ustadz) managing small pesantren, prayer groups, or study circles.

The Role of Pesantren

During his research, Pelletier conducted numerous interviews with kiai and members of militant groups, while also utilizing recent data on 15,000 pesantren and 30,000 kiai across Java. His comparative analysis provided fresh insights into the landscape of Islamic institutions in Java.

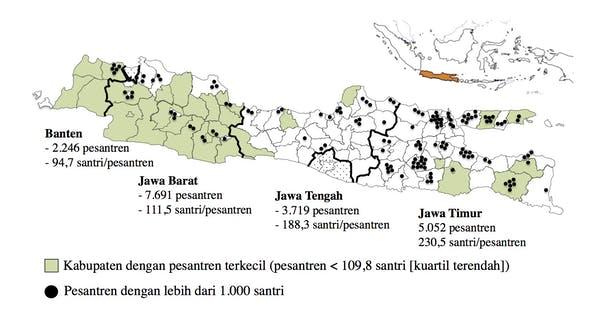

Pelletier’s comparison revealed that while West Java has more pesantren than East Java, the average size of West Java’s pesantren is significantly smaller (WB=111.5 students; EJ=230.5 students). A map produced by the research shows districts with smaller pesantren (marked in green) and those with pesantren enrolling more than a thousand students (marked with black dots) across Java.

In West Java, pesantren tend to be smaller than in other regions. There are only 26 pesantren with over 1,000 students in West Java, compared to 94 in East Java.

This comparative mapping indicates that despite having more pesantren, those in West Java wield weaker authority compared to their counterparts in East Java. In West Java, pesantren are not only smaller but also collectively weaker. The networks between kiai in West Java are more fragmented, informal, and less cohesive than in East Java.

Another important finding from this study concerns the organizational dynamics of religious institutions in West Java. While many people in West Java identify with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia, NU is neither dominant nor highly influential in this region. Instead, West Java’s Islamic organizational landscape is highly fragmented. Most kiai are either unaffiliated or members of smaller organizations.

From these comparative insights, Pelletier concludes that in West Java, religious elites and institutions have weaker authority, and the competitive nature of this structure creates a fertile environment for the growth of radicalism.

Translated from here.